Among the noble allies of alchemy and accomplices of high art there lay in parasitical wait a coterie of unsavory swindlers. These poisonous peddlers of creative cozenage foul the rarified troposphere of our sublime culture. For every Lionel Trilling there's at least half a dozen Vissarion Belinskys and each Fairfield Porter comes with the value added tax of a boatload of Horace Ben Davenports. (Davenport, for those who have forgotten, was, together with Franck and Pissolle the three resident art critics for the 1940's French collaborationist periodical "Notre Culture Pur")

One notable exception to this cruel principle of diminishing returns was the illustrious and now lamentably defunct Parisian monthly, Taide.

Never before nor since has there been such a fine collection of scholars, critics, historians and artists working in such close collaboration toward the goal of discussing the world of ideas. The Partisan Review with its political infighting and petty rivalries pales in comparison to Taide. Bazin's macho band of bullies in Cahier du cinéma are a waxen shroud of recycled orthodoxies when stacked up against the intrepid intellectuals of Taide.

Between the magazine's inception in 1976 until its last issue in 2004, writers like Barney Aleksić, Gavriel Carrá, Nadya Bugaud-Tzvi, Loie Garaudy, just to name a few, were highly revered household names throughout the French speaking world.

Soaring above the pact in both his intellectual range and in his grace as a human being was the late British philologist, Richard Ypres. Though he spoke and wrote in the most eloquently mellifluous French, when he published his work in Taide he always worked in close collaboration with his translator wife, Martine Poplout.

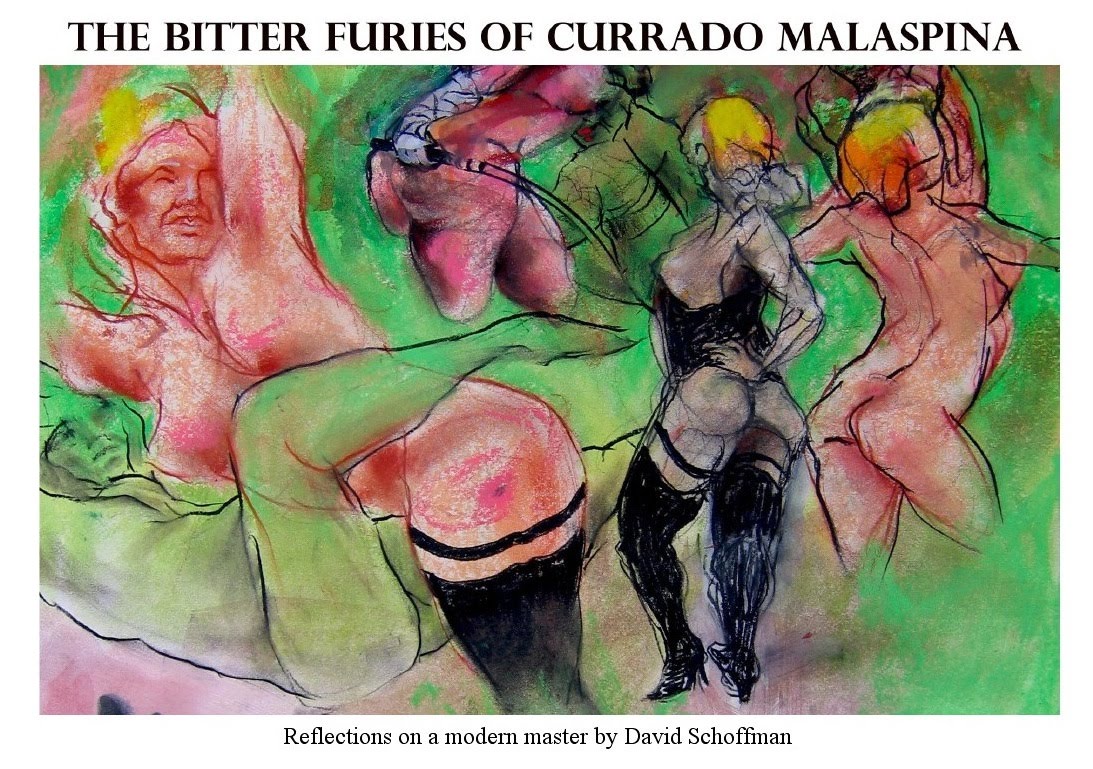

When they visited Currado Malaspina's studio in the winter of 2003, they spent a full week researching, interviewing, reflecting, inquiring and speculating in order to compose a thorough rendering of his oeuvre and his place in the canon of 20th century modernism.

Featured in the February 2003 issue, the sixteen page essay, "Suit d'un etat d'ivresse," (loosely, "Following a Bender") was a highly critical close reading of Malaspina's entire career. Beautifully written - Martine is also a well known writer of fiction, most notably the best seller "Théorie Rudimentaire" (Totou Presse 1999) - "Suit d'un etat" quickly became a classic in its genre.

Unlike his late friend Perec, Malaspina's disdain for critics is not an all consuming dismissal of the "leeching ancillary fringes of artistic invention."

As he wrote to me several years ago in a letter filled with uncharacteristic grace, "I salute and applaud our intrepid illuminators, our expert annotators, our pundits and expositors and I invite and encourage them to shed their lucent wisdom on my work."

One notable exception to this cruel principle of diminishing returns was the illustrious and now lamentably defunct Parisian monthly, Taide.

Never before nor since has there been such a fine collection of scholars, critics, historians and artists working in such close collaboration toward the goal of discussing the world of ideas. The Partisan Review with its political infighting and petty rivalries pales in comparison to Taide. Bazin's macho band of bullies in Cahier du cinéma are a waxen shroud of recycled orthodoxies when stacked up against the intrepid intellectuals of Taide.

Between the magazine's inception in 1976 until its last issue in 2004, writers like Barney Aleksić, Gavriel Carrá, Nadya Bugaud-Tzvi, Loie Garaudy, just to name a few, were highly revered household names throughout the French speaking world.

Soaring above the pact in both his intellectual range and in his grace as a human being was the late British philologist, Richard Ypres. Though he spoke and wrote in the most eloquently mellifluous French, when he published his work in Taide he always worked in close collaboration with his translator wife, Martine Poplout.

When they visited Currado Malaspina's studio in the winter of 2003, they spent a full week researching, interviewing, reflecting, inquiring and speculating in order to compose a thorough rendering of his oeuvre and his place in the canon of 20th century modernism.

Featured in the February 2003 issue, the sixteen page essay, "Suit d'un etat d'ivresse," (loosely, "Following a Bender") was a highly critical close reading of Malaspina's entire career. Beautifully written - Martine is also a well known writer of fiction, most notably the best seller "Théorie Rudimentaire" (Totou Presse 1999) - "Suit d'un etat" quickly became a classic in its genre.

Unlike his late friend Perec, Malaspina's disdain for critics is not an all consuming dismissal of the "leeching ancillary fringes of artistic invention."

As he wrote to me several years ago in a letter filled with uncharacteristic grace, "I salute and applaud our intrepid illuminators, our expert annotators, our pundits and expositors and I invite and encourage them to shed their lucent wisdom on my work."