It all started innocently enough when an ecclectic group of French artists and intellectuals gathered around a table the size of a small aircraft carrier. It was 1999 and the city of Paris was celebrating la fête de Pâques. The generous art patrons Alois and Brigitte Ormontagne were hosting their annual seder de Pessach for about 65 of their most intimate friends. Among the guests were Ludovic Halévy, Henri Blowitz, Alponse Halimi and his wife Ysmin, the Derridas, Zazie Modiano, Nathalie Artem, Solange Dreyfus-Meyer and my good, catholic friend Currado Malaspina.

Amid teeming platters of legumbres yenos de karne, arroz de sabato, berenjenas ahobadas, carpe à la juive (sometimes known as gefilte fish) and gallons of respectable Galilean wine, this pack of European intellectual luminaries held forth on subjects both sacred and profane. Currado was particularly taken by the participation of the children - the poet Anouk Atata's five year old daughter Chantalle recited the four questions without a flaw - and by the exegetical drama that was sustained throughout the interminable meal.

By the time they poured the ritual 16th glass of wine (Currado was under the mistaken impression that the ceremony demanded four cups but he was assured by his hosts that any multiple thereof was fine), most of the participants were pretty giddy and some were even advocating the Pharaoh's position in the bible's most famous labor dispute.

When former Algerian Foreign Minister Quentin Zhoof spilled half his 1984 Yatir Tishbi syrah over Alois' Haggadah, everyone took it as a signal to bring the festivities to a close. But Currado, (who by the way, does not drink), saw in this clumsy mishap a wonderful artistic opportunity. The wine-stained pages with their arcane typography and indecipherable alphabet struck him as an object of remarkable beauty. He insisted to his hosts that if he were allowed to take this brittle 19th century volume back to his studio he would delicately restore to its original state. This holy book had been brought to Paris from Bukovina by Ormontagne père in 1938 and was Alois' only link to a side of his family that perished during the War. He was nervous but grateful by Malaspina's thoughtful offer.

Currado never did get around to returning the book and Ormontagne was too much of a gentleman to demand its repatriation. I heard that Malaspina cut it up and used its pages as drawing paper. Some even suggested that he sold it to a collector of rare books in New York who subsequently donated it to a religious library in Jerusalem.

Whatever the truth is, one thing is clear:

|

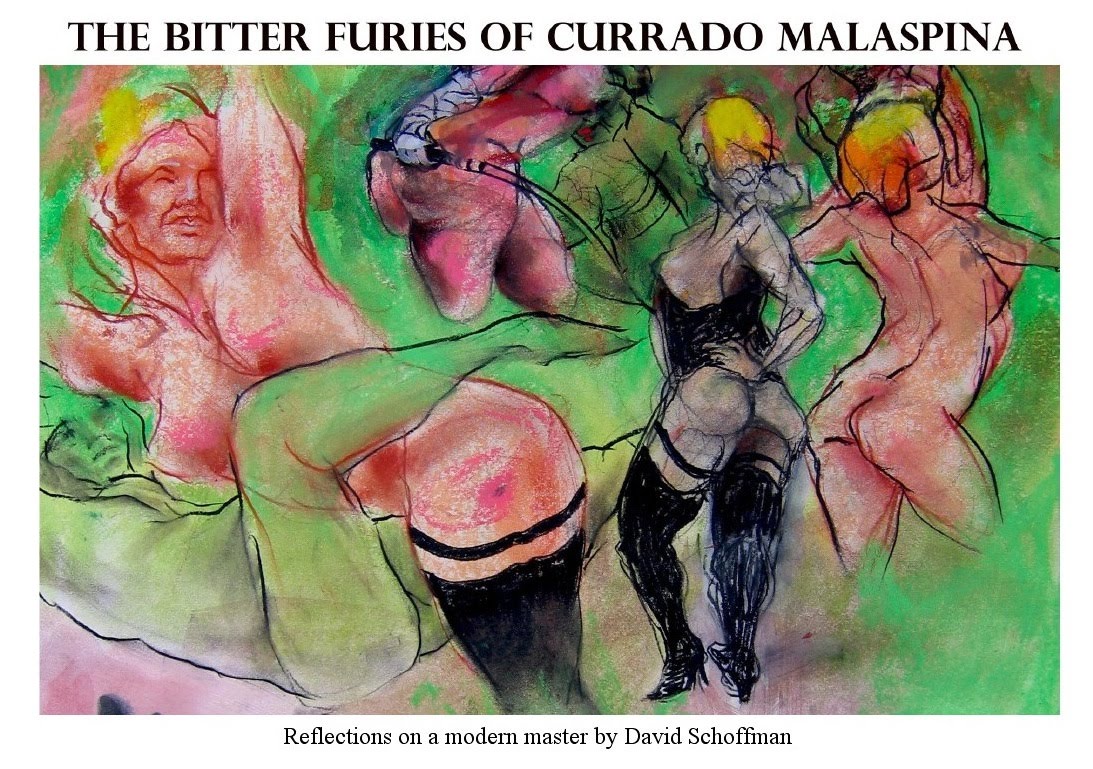

| Palimpseste II no.3, Currado Malaspina, 2002 |