My good friend Currado Malaspina has reached the tender age where his retrospective eye is no longer jaundiced by regret and his prognosticating eye is no longer fouled by expectation.

He has reached the age of sanguinity.

He has a lovely girl-friend with whom he shares a gentle intimacy, he has a brilliant editor with whom he has a deep and abiding friendship and he has a temperamental wife in whom he has a reliably nimble adversary.

In other words, like many artists before him he is leading what the French call la vie bohème en rupture.

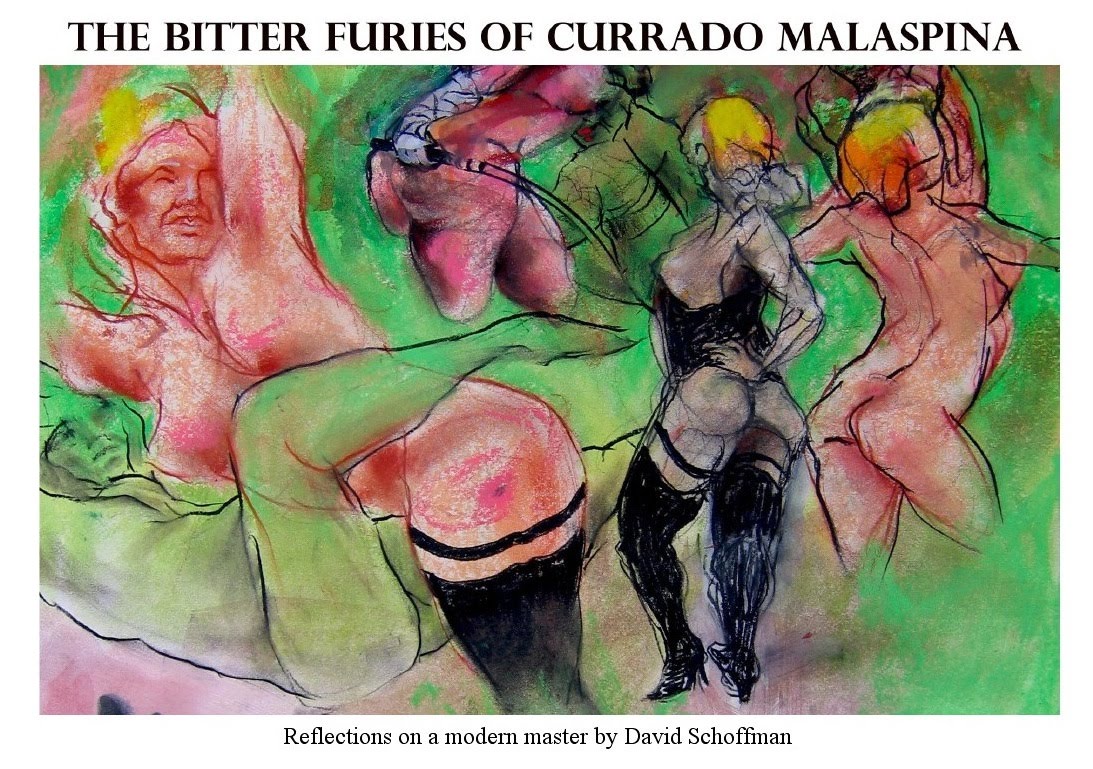

.jpg) As he withdraws into the predictability of habit and the near abjuration of conspicuous vice his work has taken a decided turn toward the staid, the complacent and, dare I say, the priggish. Where once he courted scandal, it is more common these days for Currado to take comfort in consensus and conformity. His induction into the august Société des grands maîtres de la république is only the most recent case in point. For the most part he seems to spend his time reading Le Monde Diplomatique, playing pétanque in Parc André Citroën with a few chain-smoking retirees and drawing the live model on Thursday nights at Ateliers Rrose Selavy in the 9ème.

As he withdraws into the predictability of habit and the near abjuration of conspicuous vice his work has taken a decided turn toward the staid, the complacent and, dare I say, the priggish. Where once he courted scandal, it is more common these days for Currado to take comfort in consensus and conformity. His induction into the august Société des grands maîtres de la république is only the most recent case in point. For the most part he seems to spend his time reading Le Monde Diplomatique, playing pétanque in Parc André Citroën with a few chain-smoking retirees and drawing the live model on Thursday nights at Ateliers Rrose Selavy in the 9ème.

The legend of Malaspina, a convenient fabrication crafted like a fine watch and nurtured like a vine has finally fallen into disuse. In this, our viral age, it's slow obsolescence has barely been noticed. The only things that seem to remain are the scars, the stories and the work.

To those still sympathetic to this mediocre man ...

pick two.

In other words, like many artists before him he is leading what the French call la vie bohème en rupture.

.jpg) As he withdraws into the predictability of habit and the near abjuration of conspicuous vice his work has taken a decided turn toward the staid, the complacent and, dare I say, the priggish. Where once he courted scandal, it is more common these days for Currado to take comfort in consensus and conformity. His induction into the august Société des grands maîtres de la république is only the most recent case in point. For the most part he seems to spend his time reading Le Monde Diplomatique, playing pétanque in Parc André Citroën with a few chain-smoking retirees and drawing the live model on Thursday nights at Ateliers Rrose Selavy in the 9ème.

As he withdraws into the predictability of habit and the near abjuration of conspicuous vice his work has taken a decided turn toward the staid, the complacent and, dare I say, the priggish. Where once he courted scandal, it is more common these days for Currado to take comfort in consensus and conformity. His induction into the august Société des grands maîtres de la république is only the most recent case in point. For the most part he seems to spend his time reading Le Monde Diplomatique, playing pétanque in Parc André Citroën with a few chain-smoking retirees and drawing the live model on Thursday nights at Ateliers Rrose Selavy in the 9ème.The legend of Malaspina, a convenient fabrication crafted like a fine watch and nurtured like a vine has finally fallen into disuse. In this, our viral age, it's slow obsolescence has barely been noticed. The only things that seem to remain are the scars, the stories and the work.

To those still sympathetic to this mediocre man ...

pick two.